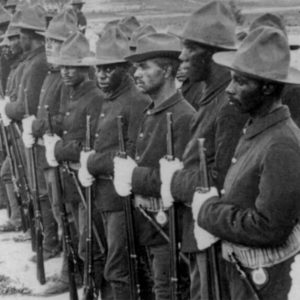

Without proper attention, history becomes the recording of selective memory rather than documentation of complete facts. Such was the fate of the deeds and contributions of the Buffalo Soldiers of the American Southwest. Unfortunately, many generations of all races were denied the opportunity to understand and appreciate these great warriors. History is now repairing itself. As if the desert wind is blowing away sand that has covered up their trails, encampments, and forts for the past one hundred years, the story of the Buffalo Soldiers is finally being unearthed.

Following the Civil War, Congress authorized the establishment of two cavalry and four infantry regiments composed of black American soldiers under the supervision of white officers. The two horse soldier regiments were designated the Ninth and Tenth Cavalry, commanded by Colonels Edward Hatch and Benjamin Grierson respectively. Both officers were extremely capable and both were also unburdened with the personal trait that was predominant on the western frontier: neither was a racist. The Ninth was initially offered not to Hatch, but to the Army’s most famous and self-serving cavalry officer. But George Custer refused the position, claiming black soldiers were inferior fighters. Because of Custer’s attitude, the soldiers of the Ninth Cavalry were much better off than their counterparts in the Seventh. Unlike Custer, Hatch was not abusive of his soldiers. Also, unlike Custer, Hatch did not wage war on sleeping villages, and never led his men to slaughter in a glory-seeking endeavor.

Unwarranted bias did not stop at the regimental commander level. Before Congress, General of the Army William Sherman stated “The blacks are a quiet, kindly, peaceful race of men”. Discipline records did verify that the black soldiers were less likely to get into trouble or desert than their white counterparts. Unlike Sherman, Hatch and Grierson did not confuse self-discipline with fighting ability.

The respect these two regimental commanders had for their soldiers was soon to be shared by Comanche and Southern Cheyenne warriors. At first, the presence of black soldiers in blue uniforms was an oddity for Native Americans. Through the sting of battle, the warriors came to realize that they were fighting a determined and skilled force such as they had ever met. First, as a means of identification, then as a statement of respect, the Comanche and Southern Cheyenne braves applied the term “Buffalo Soldiers” to this force. Rather than take offense, the soldiers embraced the name, applying the term to themselves.

After serving in the mid-west, the two regiments were transferred. Hatch’s Ninth assumed responsibility of various posts in New Mexico. Grierson’s Tenth first took up positions in western Texas and eventually moved to Arizona. Both regiments began a tour of duty never seen before or since. Their area of operation consisted of American territory populated by three cultures and races stacked upon each other. On both sides of the Mexican border, the original residents were members of the Apache nation. Not since the Mohawks had the United States seen such independent and fierce fighters as the Apaches. Because of their ferocious independence, Apaches were never able to band themselves together in great numbers like the Sioux and Cheyenne. This was very fortunate for the settlers who came to the area.

Onto the lands claimed by the Apaches, first came the Hispanics. With the exception of a dozen years following the Pueblo Revolts, their presence had been growing since the 1600s. Two hundred years later came the Anglos. With the Pueblo Revolt and Taos Rebellion serving as grim reminders, conflict between any two of the three could result in heavy bloodshed. Just as Native American tribes were subject to warring among themselves, range wars among the Anglos were not uncommon. Three races, three separate cultures, coming from three parts of the world, all in one land. It is ironic that the task of bringing peace to this land was given to a fourth race, the one which had suffered the most from western civilization.

If hostility among the population wasn’t bad enough, the environment added to the situation. In their new assignment, the Buffalo Soldiers had left behind the tall grass and trees of the western plains for sand and cactus. They now had to survive in blazing heat and bitter cold, patrolling desert floors and mountain ranges, suffering in dust storms and ice storms, experiencing drought and flash floods, and living among scorpions and rattlesnakes. The Buffalo Soldiers had left behind a much more hospitable natural environment. The one thing they were not able to leave behind was the racial intolerance born out of an environment of ignorance, bigotry, and hate. Their presence in New Mexico was recognized by a Las Cruces editor who recommended that the Ninth Cavalry be disbanded and its soldiers used to “contribute to the nation’s wealth as pickers of cotton and hoers of corn, or to its amusement as a traveling minstrel troupe.”

As unjustified as this statement was, its timing was even worse. The Ninth, soon to be supported by the Tenth, was engaged in defending New Mexico settlers against Victorio. Next to Cochise, Victorio was the most powerful and skilled warlord of the Apache Nation. Victorio had been forced into a devil’s alternative. Indian agent John Clum, who would later as mayor of Tombstone, give political support to the Earp brothers, decided to move the Apaches to a barren Arizona reservation. Victorio was left with two choices: his people could either starve to death on government reservations, or he could lead them away. While the former offered no hope, the second offered the chance to hunt. Victorio chose the latter and led 300 followers off the Ojo Caliente Reservation. Had Victorio simply left, he would not have been aggressively pursued. He and his followers went on the warpath, continually slashing trails of death across southern New Mexico. Victorio, like many great warlords of the ages, understood the concepts of mobility and personal leadership. His knowledge of the country and his ability to move back and forth across the U.S./Mexican border allowed him to elude the armies of both nations.

At first, Victorio was pursued only by members of the Ninth Cavalry, led by the very capable Major Albert Marrow. Numerous skirmishes kept Victorio on the run and prevented a total reign of terror. However, the territory was also too big for one command to protect. Solving this problem, Grierson moved his Tenth into New Mexico to support Hatch. To avoid certain capture, Victorio once again escaped into Mexico with the intent to return through Texas. Victorio was now at war with the most skilled adversary he would ever encounter – Grierson. Writing his own rules-of-engagement, Grierson stationed ten-man detachments of Buffalo Soldiers at every west Texas watering hole. With a pursuit force ready to ride, he waited for Victorio.

Grierson knew his risk. By assigning small detachments to stand between water and a three-hundred member Apache war party until he could arrive with the main body, Grierson was basically asking the same thing that Travis had forty years earlier at the Alamo. Yet, when the series of conflicts were over, the Buffalo Soldiers did not suffer a single desertion, nor lose one watering hole. With Grierson’s main body always on his heels, Victorio finally fled for the safety of Mexico.

Victorio’s feeling of safety after crossing the Rio Grande was short lived. Making a decision that would one day be copied in John Wayne’s cavalry classic “Rio Grande,” Grierson risked court-martial and followed Victorio into Mexico. Grierson and his Buffalo Soldiers were tired of the slaughter. For Grierson and his troops, enough was enough. They had risked their lives every day in pursuit of Victorio. They made the decision that risking their careers was a comparatively small price to pay to bring peace to the western frontier. Joining forces with the local Mexican Army commander, Grierson was finally able to pin Victorio down in a box canyon.

While both armies prepared for the final fight, Grierson was instructed to return his forces to the United States. As the Buffalo Soldiers returned across the Rio Grande and back into the United States, in the fight with the Mexican Army, Victorio crossed the great divide that separates life and death. Although denied the opportunity to participate in the final destruction of Victorio’s band, it was the Buffalo Soldiers who chased them into the jaws of death.

The deeds of the Buffalo Soldiers were not limited to battles against Victorio and his successor, Nana. Buffalo Soldiers were directly or indirectly involved in the Lincoln and Catron County Wars, provided exploration and mapping of the southwestern frontier, protected trails and railroad crews, removed unlawful settlers from reservation lands, and fulfilled every other task expected of American soldiers. Their efforts in the southwest earned them several Congressional Medals of Honor. Despite Sherman’s comments before Congress, the Buffalo Soldiers proved themselves to be far more than a quiet, kindly, peaceful race of men. They proved themselves to be world-class warriors, equal to the reputation they had earned among the Comanche, Cheyenne, and Apache nations.

Yet, despite how great the feats and how well they served, the Buffalo soldiers were condemned by many of the same people they protected. It was during the campaign against Victorio that one of the most blatant acts of discrimination and disrespect occurred. While on patrol, Corporal James Betters died. His body was returned to Fort Bayard for burial. When his fellow troops returned to the fort, they learned their comrade had been hauled to the cemetery in a cart used for garbage and driven by a convict. Betters’ commander, Captain Beyer, demanded an investigation. The demand was fulfilled, but no action was taken against those responsible.

Many years after leaving the southwest, Buffalo Soldiers were summoned to the Battle of Wounded Knee. The legendary 7th Cavalry was once again surrounded and on the verge of suffering a defeat greater than the one Custer had led them into twenty years earlier. In a twist of fate, the very group that Custer once refused to lead would deliver the command he did accept from certain annihilation. For heroic service in this action, the Buffalo Soldiers earned yet another Congressional Medal of Honor. At a time when the western frontier was like a series of powder kegs spread over a vast region, with fuses that were often ignited, it was the Buffalo Soldiers who prevented the explosion. For a generation of the west’s most turbulent years, these Americans provided stability. Finally, when their mission was successfully completed, they were denied the legacy they had earned.

The last of the western frontier Buffalo Soldiers have long since passed from our ranks. Each has been returned to the earth from which they came, and over which they patrolled. No professional force of soldiers has ever endured the never-ending difficulties faced by the Buffalo Soldiers. They stood against the elements of nature and the hostility of mankind. Most had been born into slavery, only to be freed in a land that offered them little. As a chance to better themselves, they accepted the uniform of the American soldier. In wearing that uniform, they served to protect the lives of others – many of whom accepted the protection while still harboring hate over the shade of a man’s skin. Yet, the Buffalo Soldiers continued to serve. It is most appropriate that they are now receiving the recognition they have always deserved. They earned the right to be remembered for their worthy contribution to the development of the United States of America.

~ Colonel (Retired) Wes Martin

Established by a Congressional Act in 1866, the African-American military division would serve on the frontier and become known as ‘Buffalo Soldiers’.

Colonel (Retired) Wes Martin

Colonel Martin’s military assignments include Senior Antiterrorism officer for all Coalition Forces in Iraq; Chief of Operations, Task Force 134 (Detention Operations); Commander of Camp Ashraf, Iraq; Chief of Information Operations, Headquarters, Department of the Army; and 123 months of command time, including two battalions and one group.